On 17 April 1345, the Great Council of the Venetian Republic repealed the law that until then had fobidden citizens of the Serenissima from purchasing land on the mainland. As a result, part of the Venetian patriciate shifted its interests from trade to the hinterland. From the 16th century onwards, canals and rivers easily accessible from Venice were lined with sumptuous summer residences.

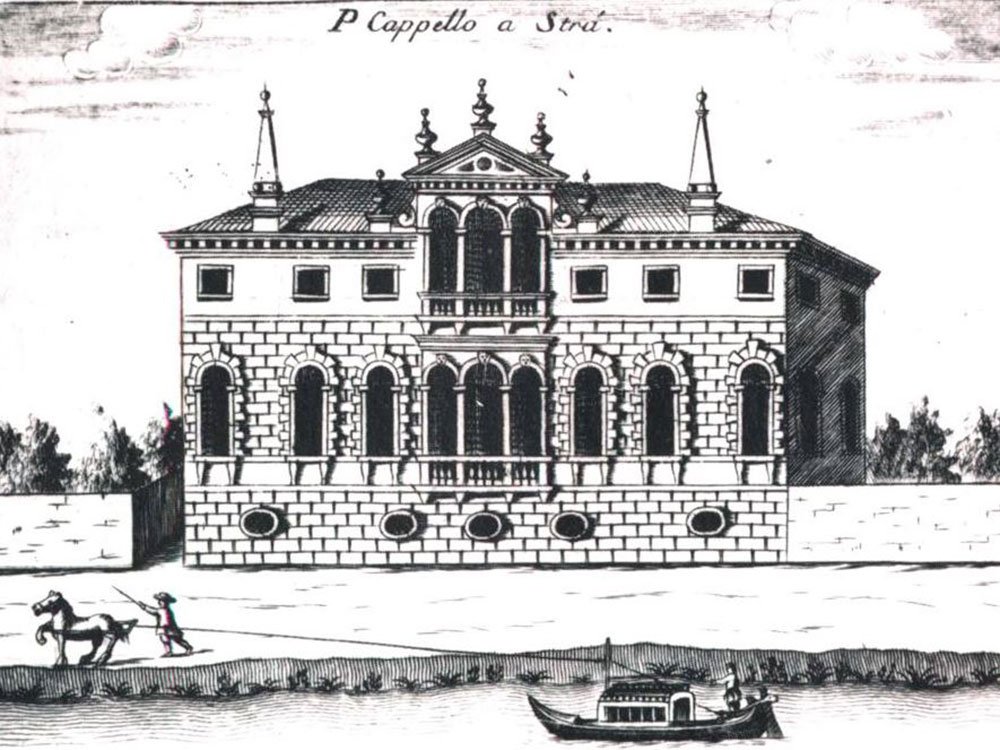

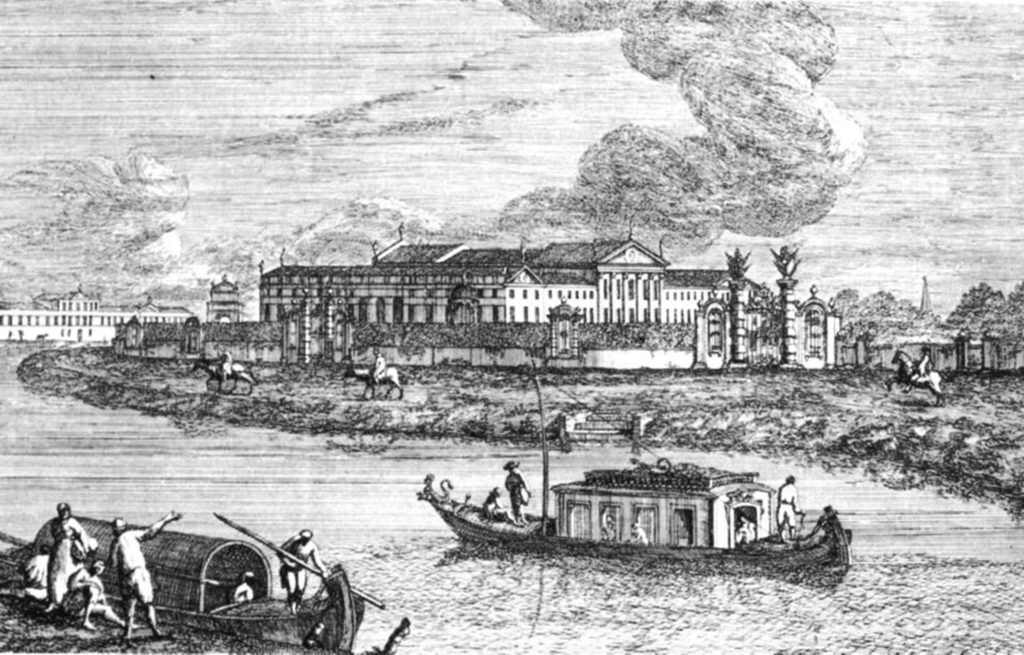

The Brenta Canal, which – together with other waterways – connected Venice with Padua, soon became the fashionable route: a place of delight and an ideal extension of the Grand Canal in Venice, where more than seventy luxurious villas flourished. Great architects, such as Palladio, Scamozzi, and Frigimelica, designed these summer residences for the Venetian nobility, who spent their “villeggiatura” period on the mainland, in a true Arcadia of ladies and gentlemen who played, sang, experienced love and told tales.

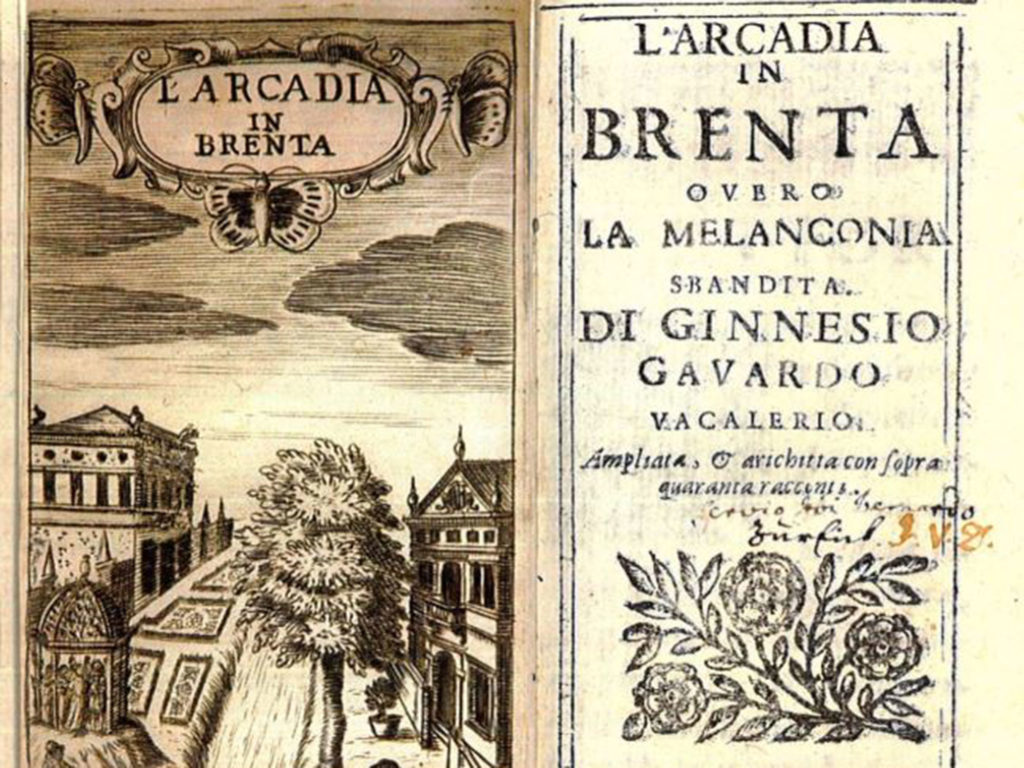

Giovanni Sagredo’s ‘L’Arcadia in Brenta’ (1667), published under the pseudonym of Ginnesio Gavardo Vacalerio, is a collection of mid-17th-century novellas, set along the Riviera del Brenta, one of the most renowned holiday destinations of the time. The work recounts eight days spent by a cheerful group of Venetian nobles among villas, gardens, fishponds, and pleasant places of that golden Arcadia.

It was here that, not far from the city, the wealthiest patricians spent their holidays, departing from Venice in comfortable luxury boats known us Burchielli, which sailed up the navigable Brenta Canal. These boats were propelled by dint of rowing from St. Mark’s Square across the Venetian lagoon to Fusina, where horses then pulled them all the way to Padua along the Brenta Riviera. The Venetian nobility also brought to the Burchiello the same elegance, refinement and luxury that characterised the city of Venice.

And it was on the Riviera del Brenta that even Carlo Goldoni, in the mid-1800s, set his “Arcadia in Brenta” – an opera buffa portraying Venetian nobles and wealthy bourgeoisie and their longing for a holiday on the mainland. The Burchiello became almost a small stage on which the most diverse social classes mingled, and Goldoni even dedicated a poem to it.

In 1574, the Brenta Canal from Venice to Padua’s Portello was travelled by a procession of boats accompanying Henry III, King of France, on his return from Poland. The king was fascinated by the beauty and monumentality of the route and later chose to stay at Villa Foscari, know as “La Malcontenta“.

Giacomo Casanova recounts in “The Story of My Life” his journey on the Burchiello along the Brenta Riviera in 1734, in the company of Baffo, a famous Venetian erotic poet.

In September 1728, having arrived in Venice, Montesquieu also boarded the Burchiello and travelled along the Riviera:

“by the Brenta, a river turned into a canal by means of four locks; thus a single horse pulls a very large boat, covering twenty-five miles in eight hours. Along the Brenta you see beautiful patrician residences. The Noble Pisani has begun one that will be extraordinarily magnificient…”

In 1786, Goethe arrived in Padua, visited the Botanical Garden and then went to Venice and described the journey along the Riviera del Brenta as follows:

“Just a few words about the journey from Padua to Venice: the navigation on the Brenta with the public Burchiello, in the company of well-behaved people (for Italians are considerate with one another), is comfortable and pleasant. The banks are adorned with gardens and pavilions, small villages look out onto the river, lined at times by the bustling main road. Since the course of the river is regulated by locks, one often has to make short stops, which can be used to stroll through the village and to enjooy the abundant fruits offered. Then we get back on the boat and continue on our way, through a lively world full of fertility and animation.”

It was the time of the villeggiatura, the feverish longing for holidays in the countryside during which, as Goldoni wrote, “everyone enjoyed immense freedom, there was great play, open tables, balls and shows”.

It was also the custom, during holiday time, to “go from villa to villa” ( “andar per ville”): lively groups moved from one residence to the next, from one party to another, amidst sumptuous receptions and sumptuous banquets that lasted up to a week.

Towards the end of the 18th century, with the fall of the Venetian Republic in 1797 at the hands of Napoleon, the hardships of the Venetian dolce vita were reflected inland; many villas closed, parties and banquets disappeared, as did the dolce vita of the Riviera del Brenta; and as the number of passengers and rides decreased, the Burchiello’s luxury scheduled service finally ceased as well. A long period of decline swept over the Riviera del Brenta.

In the 1950s, with the first tourist movements, an interest in rediscovering the Riviera began. After 150 years, in 1960, the Padua Provincial Tourist Board rediscovered and re-proposed the Burchiello line service as a tourist itinerary, thanks to a happy intuition of its director Francesco Zambon. The new Burchiello scheduled service was inaugurated in 1962 by the then President of the Italian Republic, Antonio Segni, and resumed with a considerable increase in passengers.

The tourism industry began to invest in important prizes and major gastronomic events. Mindful of the great banquets in villas, handed down through history, they recovered and revived much of the prestigious capacity for preparing seafood specialities that had been lost in the waning days. Little by little the osterie became trattorias and restaurants, the villas were partly restored and new accommodation facilities sprang up; some historic residences were opened to visitors, others became hotels, others venues for meetings and parties; the tourist movement grew and so did the myth of the Riviera del Brenta.